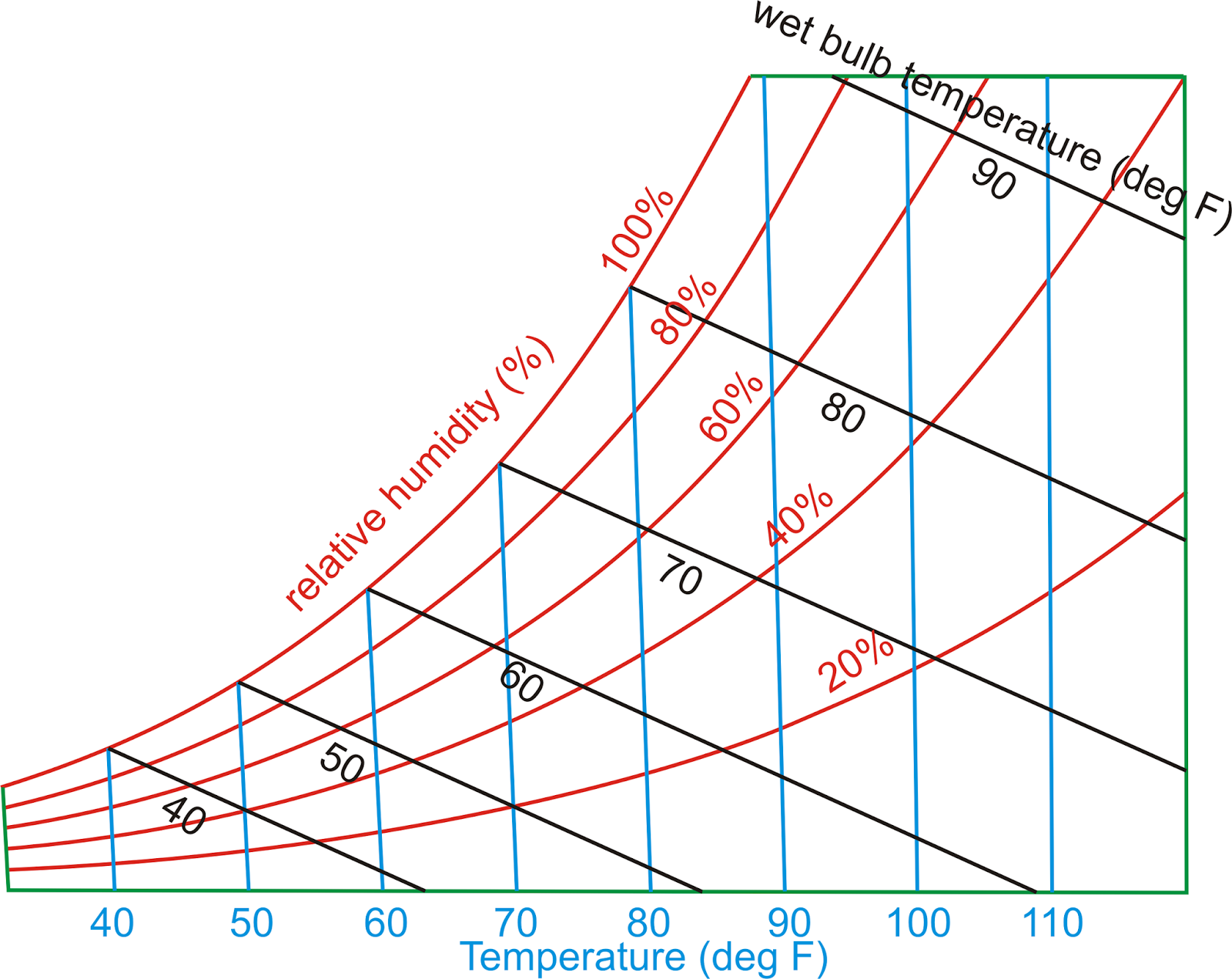

On the psychrometric chart, the air follows a line of constant wet bulb temperature during an evaporative cooling process. These lines go from lower right to upper left across the chart.

As the liquid water is evaporated into the air, the air increases in humidity ratio, and drops in temperature. Obviously, no more water can be evaporated once the moist air reaches the line of 100% relative humidity. So evaporative coolers work best in hot, dry climates (hence, the name “desert coolers”) because there is potentially a much larger temperature depression. Immediately after leaving the cooler, the air will be at a much higher relative humidity than it started at, and may feel muggy—hence the name “swamp coolers”.

This figure shows the maximum possible temperature depression available as a function of the temperature and relative humidity of the incoming air.

No comments:

Post a Comment